If Everything’s so Great, Why Are New Orders Cratering?

New Orders are in recessionary territory.

The financial news is astonishingly rosy: record trade surpluses in China, positive surprises in Europe, the best run of new jobs added to the U.S. economy since the go-go 1990s, and the gift that keeps on giving to consumers everywhere, low oil prices.

So if everything is so fantastic, why are new orders cratering? New orders are a snapshot of future demand, as opposed to current retail sales or orders that have been delivered.

Like most other economic data, the series is noisy, meaning there are plenty of spikes up and down. To cut through the clutter, we look for trends and patterns, i.e. what did the series do prior to past recessions?

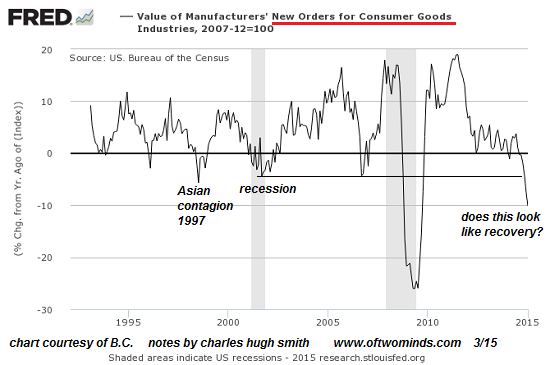

The answer is of course that new orders declined sharply. Take a look at this chart of new orders for consumer goods:new orders has reached levels below those recorded in the 2000-2002 recession.

New orders have spiked down briefly in non-recessionary periods, for example during the Asian Contagion of 1997 and a spot of weakness in 2006. But the current readings are significantly lower than these weak patches.

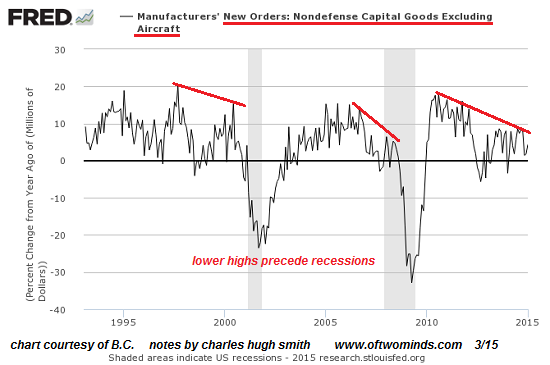

New orders for capital goods (excluding defense and aircraft orders) are not quite in recession territory, but the trendline is definitely weakening. Such weakening trends characterize pre-recessionary periods.

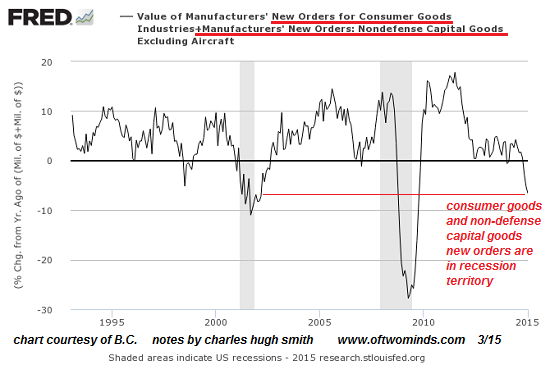

If we combine the two data series, we find New Orders are obviously in recessionary territory. Now maybe this is a temporary spike down that will be reversed next month, but if it is not reversed quickly, it is clearly divergent from the happy story of more jobs, global growth is picking up, etc.

New Orders is one side of the story; the other is real (inflation-adjusted) household income. Without more income, households must borrow more to consume more, and debt-dependent consumption eventually leads to households that can no longer borrow more, and an increasing number of households at risk of defaulting on their loans for vehicles, college, homes, credit card debt, etc.

In a period of strong global expansion, we’d expect to see median income rise not just in nominal terms but in real purchasing-power terms. But median income is still below levels reached in 2000. Courtesy of Doug Short:

In nominal terms, median household income is up a third from 2000–a strong showing indeed. But adjusted for official inflation (which understates inflation in key sectors such as healthcare and higher education), income has risen off the bottom (9.6% beneath 2000 levels) and is now only 3.9% below 2000 levels, but this is dismayingly at odds with the happy story of nominal gains.

This broad measure of household income doesn’t tell us how much of the gains have been captured by the top 10%; the top layer may have gained much more than the 90% below.

This also doesn’t reflect other potentially negative factors such as higher healthcare deductibles that lower actual take-home pay.

While “recovery” cheerleaders are busy predicting strong growth in wages going forward, they conveniently ignore that it will take another 4% of real gains just to get back to the levels of 15 years ago.

Leave a Reply