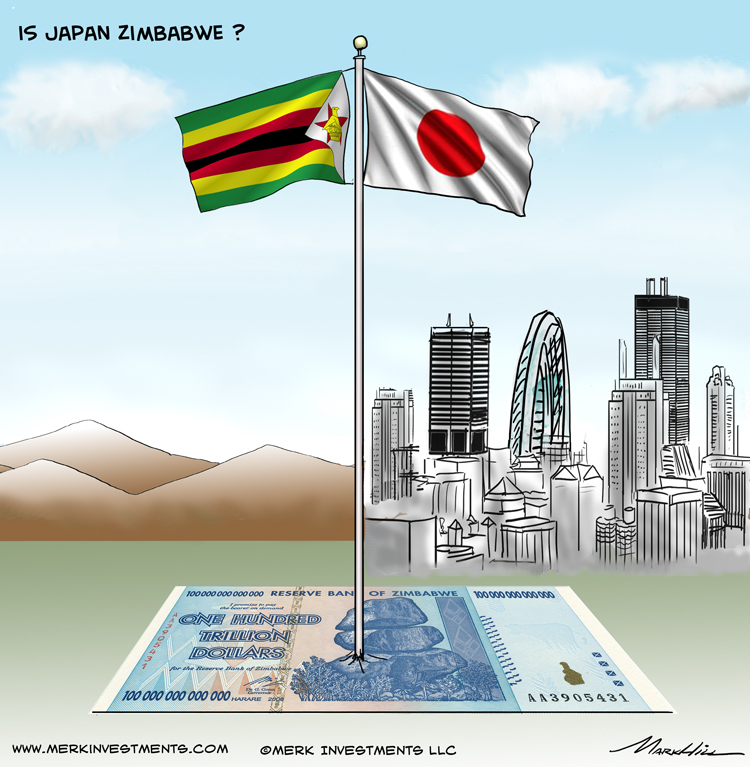

Is Japan Zimbabwe?

Is Japan Zimbabwe? How preposterous: Japan is an advanced economy that cannot possibly suffer the same fate as Zimbabwe. Right? Or could Japan get hyperinflation? Below I explain why Japan, and with it investors’ portfolios, might be at risk.

The other day, when I was on a panel discussing unsustainable deficits in the U.S., Eurozone and Japan, the risk of inflation and Zimbabwe style hyperinflation came up. When asked about the difference about Japan and Zimbabwe, I quipped that there isn’t any. My co-panelists were all over me, arguing Japan is different. Notably that Japan could not possibly go broke because, unlike Zimbabwe, it’s an advanced economy. The argument being that Japan produces goods the world wants.

To be clear: Zimbabwe and Japan are not the same. But are they really that different? Zimbabwe not only had a much weaker economy, but also much weaker institutions. But the old adage that something unsustainable won’t last forever may still hold.

The difference between Zimbabwe and Japan – and Europe and the U.S. for that matter – is that advanced economies have more control over their destiny. However, all these regions have made commitments they cannot keep by continuing business as usual. A weak country may simply implode. A strong country has choices. The preferred choice these days appears to be to kick the proverbial can down the road.

Currently, to get the country out of its malaise, Japan is trying the three arrows of Abenomics, a combination of government spending, monetary easing and structural reform. Except, of course, when the first two arrows are deployed, there’s little incentive left for the third. Structural reform is a codename for the tough choices that need to be made to get an economy to be more competitive, including flexible labor markets and less regulation.

Because the Bank of Japan gobbles up dramatic amounts of debt, the cost of financing government spending stays low. It’s been said that a country that issues debt in its own currency cannot go broke. Theoretically that may be correct: the central bank can always monetize the debt, i.e. buy up any new debt being issued. But in practice, there has to be a valve. In my assessment, that valve is the currency. Hence my prediction is that the yen will reach “infinity” versus the dollar (a ‘higher’ yen represents a weaker currency), i.e. be worthless at some point.

The path an advanced economy with unsustainable finances takes is in many ways a cultural and political question. Unsustainable government finances tend to be accompanied with unsatisfied citizens that have seen their standard of living erode, either because inflation has eaten away their purchasing power or because the government has taken away benefits. Such an environment is fertile ground for populist politicians to be elected. In the U.S., this may be the rise of the Occupy Wall Street or Tea Party movements. In Japan, a populist prime minister is in power.

What officials have in common is that they rarely blame themselves, but seek to shift blame on the wealthy, a minority group or foreigners. It’s no co-incidence that Abe wants to abandon Japan’s pacifist constitution; if Japan were able to balance its books, I allege that odds of such a discussion would be much lower. Similarly, by the way, Ukraine would not be in its current mess if it were able to balance its books. Japan unlike Ukraine, though, has well functioning government institutions.

Raising taxes is another way to try to get deficits under control. And indeed, Japan has tried, by increasing its value added tax (VAT); except that the government has shied away from another increase because of the negative impact the recent rate hike had on consumption. Broad based consumption (or energy) taxes are the only types of taxes that even have a chance of coming close to raising the orders of magnitudes needed to stuff huge fiscal holes. It’s not surprising that Scandinavian countries all have very high consumption taxes to finance their welfare states.

The most obvious choice, of course, for a government with unsustainable finances would be to cut expenditures. But it’s only Germany that appears to have embraced austerity.

Inflation is a slow motion form of default. The “advantage” of inflation, as long as it doesn’t turn into hyperinflation, is that it is less prone to the so-called “contagion.” In a default the risk is that many solvent players are drawn into insolvency as a house of cards implodes.

The reason why a government default tends to start out as a slow motion locomotive before it falls off a cliff is because stakeholders want to buy time. In the Eurozone debt crisis, for example, risk-averse investors were caught off guard when they realized their peripheral Eurozone debt was not risk free. By now, everyone should know these securities are not risk free which reduces the risk of contagion, as these assets have mostly moved away from financial institutions to those that can bear the risk. No one is going to cry if a hedge fund loses money; similarly, if the International Monetary Fund (IMF) loses money, the losses are ‘socialized’.

Back to Japan: Japan can continue on its current course as long as the market lets it. It’s impossible to predict if and when the market might lose confidence. The Eurozone debt crisis has shown that sentiment can switch rather suddenly, even for countries with fairly prudent long-term debt management, such as Portugal or Spain. It may be naïve at best to think that there will be plenty of warning should market sentiment shift.

What we do know is that central bank actions have masked risks. Risky assets don’t appear risky anymore. But of course they are still risky. So when volatility surges – for whatever reason, investors might flee with a vengeance. A default, by the way, is not the end of the world. While the socio-economic impact on a country may be severe and a default may cause institutions to fail, especially those that own debt of the defaulting country, the reset button of default doesn’t affect everything. Government institutions may survive and so may many manufacturers. Japan induced hyperinflation to hit the reset button after World War II. Who says this can’t happen again?

Japan continues to have choices how it wants to deal with its deficits. The current ‘muddle through’ environment may actually be one of the better stages. If Abenomics succeeded and real economic growth ensued, government debt would likely fall. Except that Japan might not be able to finance itself should the average cost of borrowing move much higher. Fear not, the Bank of Japan could always step in to lower the cost of borrowing yet again. In my view, that’ s a possible scenario of when the yen is going to cave in.

There’s another difference between Japan and Zimbabwe: a default in Zimbabwe doesn’t cause ripple effects in financial markets. But a Japanese default may be orders of magnitude larger than the trouble that emanated from the collapse in Cyprus. Hedging the currency risk out of the Nikkei may not do the trick. Indeed, there’s no simple way to prepare for an outcome where one doesn’t know for sure what path Japan is going to take. Some buy the Nikkei, currency hedged. Others short Japanese government bonds. Yet others short the yen. Many more do none of the above as the timing is ‘too difficult.’ Each one of these choices – including doing nothing – comes with their own set of risks; please note that this sampling of choices is not investment advice.

Reprinted with permission from Merk Investments.

Leave a Reply