Ragin’ Contagion: When Debtors Go Broke, So Do Mercantilist Exporters

Beneath the endless twists and turns of Greece’s debt crisis lie fundamental asymmetries that doom the euro, the joint currency that has been the centerpiece of European unity since its introduction in 1999.

The key imbalance is between export powerhouse Germany and its trading partners, which run large structural trade and budget deficits, particularly Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain.

Those outside of Europe may be surprised to learn that Germany’s exports ($1.5 trillion) are roughly equal to the exports of the U.S. (1.6 trillion), and compare favorably with China’s $2.3 trillion in exports, given that Germany’s population of 81 million is a mere 6% of China’s 1.3 billion and 25% of America’s population of 317 million.

German GDP in 2014: $3.82 trillion

Chinese GDP in 2014: $10.36 trillion

U.S. GDP in 2014: $17.42 trillion

Germany’s dependence on exports places it in the mercantilist camp, countries that depend heavily on exports for their growth and profits. Other (non-oil-exporting) nations that routinely generate large trade surpluses include China, Taiwan and the Netherlands.

While Germany’s exports rose an astonishing 65% from 2000 to 2008, its domestic demand flatlined near zero. Without strong export growth, Germany’s economy would have been at a standstill. The Netherlands is also a big exporter (trade surplus of $33 billion) even though its population is relatively tiny, at only 16 million. The “consumer” countries, on the other hand, run large current-account (trade) deficits and large government deficits. Italy, for instance, runs a structural trade deficit and its total public debt is a whopping 137% of GDP.

Here’s the problem when debtor/importer eurozone members such as Greece go broke and default: Who is left standing to buy all the mercantilist exporters’ goods? Ultimately, much of those goods were purchased with debt, and when debtor nations default, the credit spigot is turned off: no more borrowing, no more money to buy Dutch, German and Chinese exports.

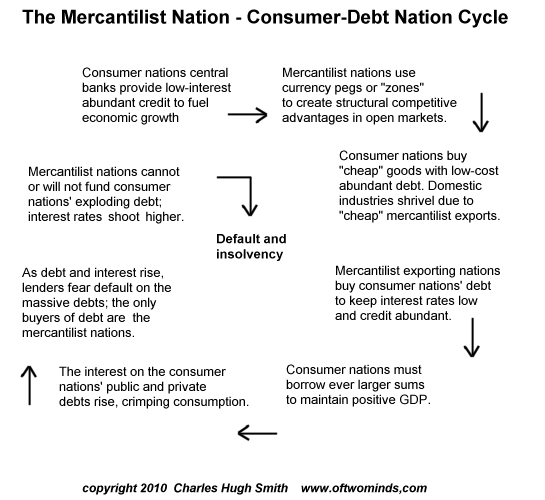

This chart illustrates the dynamic between mercantilist and consumer nations:

Although the euro was supposed to create efficiencies by removing the costs of multiple currencies, it has had a subtly pernicious disregard for the underlying efficiencies of each eurozone economy.

Though German wages are generous, the German government, industry and labor unions have kept a lid on production costs even as exports leaped. As a result, the cost of labor per unit of output — the wages required to produce a widget — rose a mere 5.8% in Germany in the 2000-09 period, while equivalent labor costs in Ireland, Greece, Spain and Italy rose by roughly 30%.

The consequences of these asymmetries in productivity, debt and trade deficits within the eurozone are subtle. In effect, the euro gave mercantilist Germany a structural competitive advantage by locking the importing nations into a currency that makes German goods cheaper than the importers’ domestically produced goods.

Put another way: By holding down production costs and becoming more efficient than its eurozone neighbors, Germany engineered a de facto “devaluation” within the eurozone by lowering the labor-per-unit costs of its goods.

The euro has another deceptively harmful consequence: The currency’s overall strength enables debtor nations to rapidly expand their borrowing at low rates of interest. In effect, the euro masks the internal weaknesses of debtor nations running unsustainable deficits and those whose economies had become precariously dependent on the housing bubble (Ireland and Spain) for growth and taxes.

Prior to the euro, whenever overconsumption and overborrowing began hindering an importer-consumer economy, the imbalance was corrected by an adjustment in the value of the importer’s currency. This currency devaluation would restore the supply-demand and credit-debt balances between mercantilist and consumer nations.

Absent the euro today, the Greek drachma would fall in value versus the German mark, effectively raising the cost of German goods to Greeks, who would then buy fewer German products. Greece’s trade deficit would shrink, and lenders would demand higher rates for Greek government bonds, effectively forcing the government to reduce its borrowing and deficit spending.

But now, with all 16 nations locked into a single currency, devaluing currencies to enable a new equilibrium is impossible. And it leaves Germany facing with the unenviable task of bailing out its “customer nations” — the same ones that exploited the euro’s strength to overborrow and overconsume.

On the other side, residents of Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Ireland now face the painful (and ultimately unworkable) effects of government benefit cuts aimed at realigning budgets with the productivity of the underlying national economy.

Either Germany and its export-surplus neighbors continue bailing out the eurozone’s importer/debtor consumer nations, or eventually the weaker nations will default or slide into insolvency. Greece is merely the first domino to fall.

Now an inescapable double-bind has emerged for Germany: If Germany lets its weaker neighbors default on their debts, the euro will be harmed, and German exports within Europe will slide. But if Germany becomes the “lender of last resort,” then its taxpayers end up footing the bill.

If public and private debt in the troubled nations keeps rising at current rates, it’s possible that even mighty Germany may be unable (or unwilling) to fund an essentially endless bailout. That would create pressure within both Germany and the debtor nations to jettison the single currency as a good idea in theory, but ultimately unworkable in a 16-nation bloc as diverse as the eurozone.

Despite endless assurances that the Greek debt crisis is contained, the reality is that the ragin’ contagion of debt crises will spread not just to other deeply indebted nations but to the mercantilist economies that depend on selling goods to borrowers. Strip out the borrowing, and you strip out most of the customers for German, Dutch and Chinese goods.

Leave a Reply