It’s Different This Time

Caterpillar (CAT) posted a disastrous 16% decline in worldwide retail sales this morning, meaning that its sales have now fallen for 35 straight months. As Zero Hedge noted, not only did US retail sales finally rollover and drop by 8% compared to prior year, but the rest of the world was a veritable bath of yellow blood:

…….. sales elsewhere around the globe were a complete debacle: Asia/Pacific (mostly China) was down -28%, a dramatic drop from the -17% a month ago, EAME dropping -13%, and Latin America down -36%…

Needless to say, this is something new under the sun. CAT is the leading heavy capital goods supplier to the global construction and mining industries and has a long history of boom and bust.

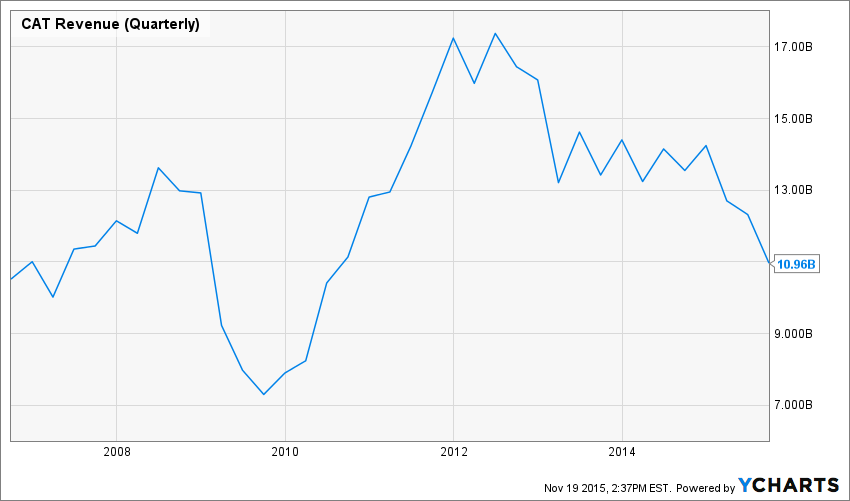

But CAT’s past contains nothing like what is conveyed in the graph below. The current 35 month plunge in its global sales is now nearly twice as longas the downturn in sales during the Great Recession, which was itself a modern record.

Indeed, CAT’s sales during the quarter ended in September had retraced all the way back to the September quarter of 2006. It is as if the massive tide of global capital spending that CAT has been riding for well more than a decade is heading back out to sea.

CAT Revenue (Quarterly) data by YCharts

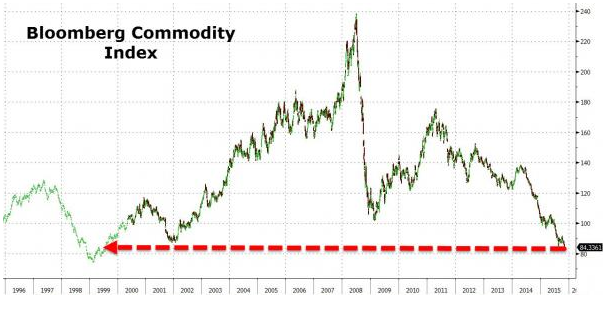

In fact, it is. The flip-side of the massive commodities boom since the turn of the century is CapEx.

That is, the tremendous increase in demand for iron ore, copper, zinc, nickel, aluminum and hydrocarbons was mainly driven by a massive one-time build-out of industrial infrastructure for mining, manufacturing, transportation and distribution—–along with related public facilities such as roads, bridges, ports, rails and airports—- in China and the EM.

Even where there were substantial increases in final demand for consumer goods—— such as appliances and autos and for the related motor fuels and household electrical power——in both the EM and DM economies, the principle impact was not in the incremental materials and energy consumed by end users; it was in the CapEx build-out of the production capacity needed to supply them.

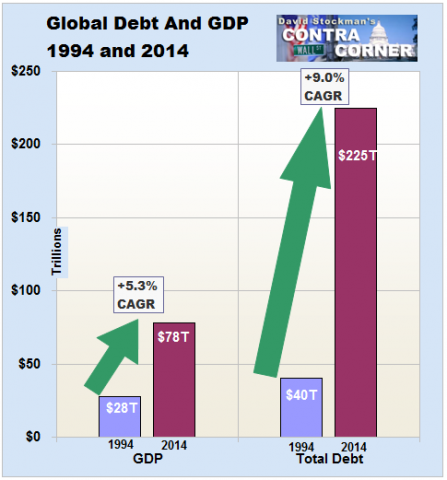

Stated differently, CapEx is extremely materials and energy intensive. What drove commodity prices to unprecedented highs earlier this century was a once-in-history CapEx boom fueled by the central bank enabled explosion of global credit.

Likewise, the virulent commodity collapse now underway is a reflection of how far the CapEx cycle overshot the sustainable requirements of the world economy. Iron ore and crude oil heading into the $30s are merely a leading indicator of the deflationary correction now underway.

But the obvious implication that $30 per ton iron ore will batter the global mining equipment industry or that $30 oil will shut down the drilling rigs in the shale patch is not the half of it. The whipsaw effect on CapEx is just getting started and it will cascade through the entire warp and woof of the global economy.

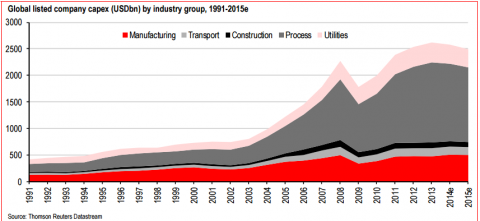

As shown below, the publicly listed companies of the world actually increased CapEx by 5X to upwards of $2.5 trillion annually during the run-up to peak capital spending in 2012-2013. Given the massive over-investment and malinvestment in the world economy, however, the drop ahead could easily amount to well more than $1 trillion annually.

Moreover, the gathering CapEx drought will last for years, even decades. That’s because the in-place value of the world’s massive surplus of factories, containerships and heavy mining and construction equipment is now vastly inflated. Accordingly, the market for used equipment and existing capacity will drop so severely that new CapEx orders will be deferred indefinitely.

Zero Hedge provided some examples from the current drastically depressed secondary market for CAT’s big yellow machines. Needless to say, a 99% off sale on existing equipment does not bode well for new orders.

Was: $2.9m | Now: $15,000: Caterpillar 992C wheel loader

Was: $2.7m | Now: $46,000: Caterpillar D11N crawler tractor

Was: $900,000 | Now: $47,500: Caterpillar 775D rear dump truck

These stunning equipment value plunges are unprecedented and give witness to the utterly aberrational nature of the commodity and CapEx cycle that has been fostered by the money printing spree of the global central banks. It bears virtually no likeness to the business cycle ebb and flow of 1981-1983 or 1990-1992 or even 2000-2002.

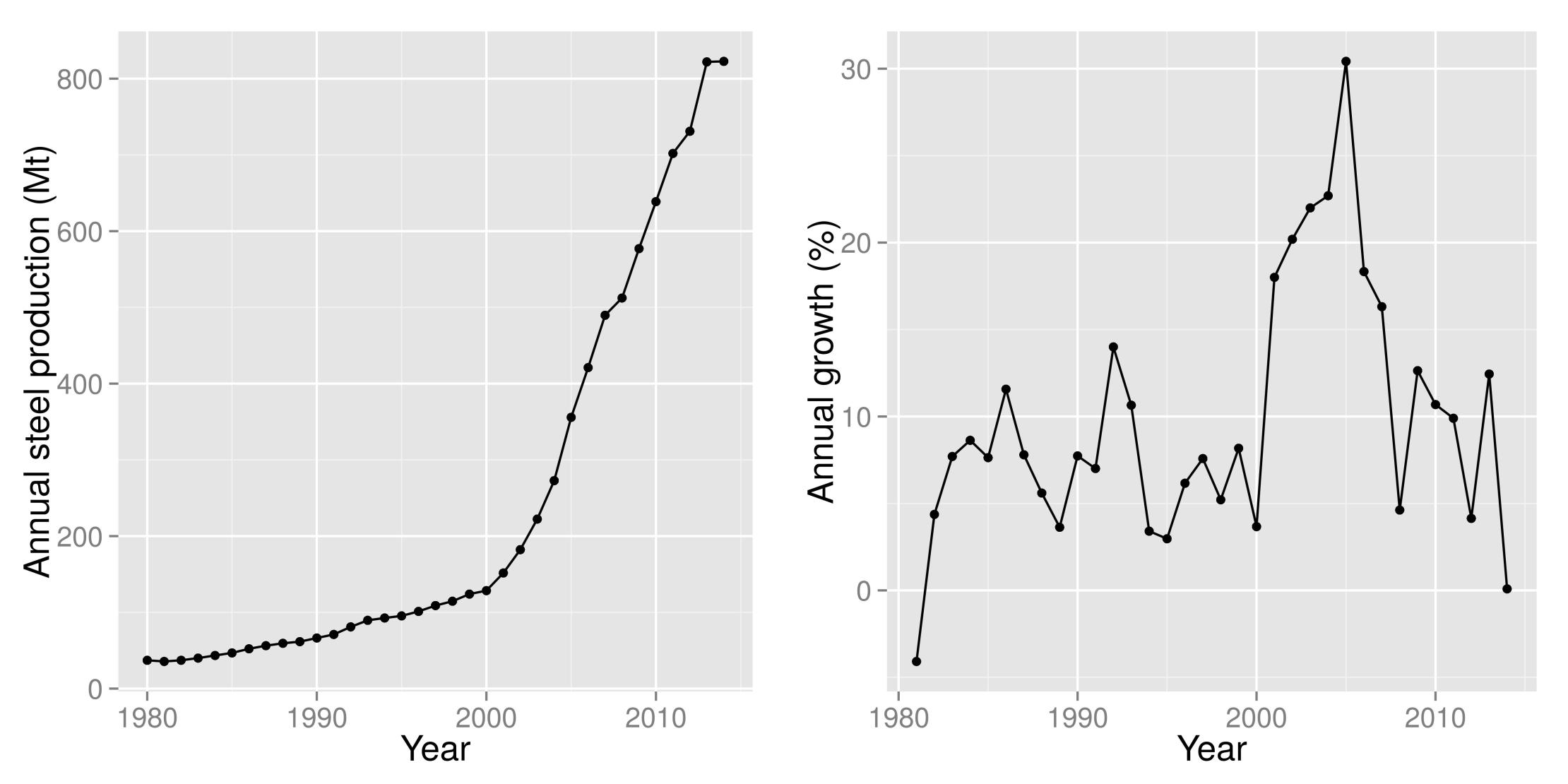

Needless to say, at the heart of the super-cycle is the Red Ponzi of China. During the last 15 years, for example, its steel production soared by 8X. On an annual throughput basis, the 725 million ton gain in steel output did cause more than a doubling of global iron ore consumption.

But it is the capacity build-out behind the above chart which tells the full story. To wit, the cheap credit enabled state steel companies of China build new capacity at an even more fevered pace than the breakneck growth of annual production. Consequently, annual crude steel capacity now stands at more than 1.1 billion tons, and nearly all of that capacity was built since the late 1990s.

This means that China’s aberrationally massive steel industry expansion created a significant increment of demand for plate, structural and other steel shapes that go into blast furnaces, BOF works, rolling mills, fabrication plants, iron ore loading and storage facilities, as well as into plate and other steel products for shipyards where new bulk carriers were built and into the massive equipment and infrastructure used at the iron ore mines and ports.

That is to say, the Chinese steel industry has been chasing its own tail, but the merry-go-round has now stopped. For the first time in three decades, steel production will be down 2-3% from last year’s peak of 825 million tons and is projected to drop to 750 million tons next year even by the China miracle believers.

The truth is there is probably not even 500 million tons per year of steady state sell-through demand for China’s steel output domestically, and it is already evident that trade barriers against export of its massive surplus are being thrown up in Europe, North America, Japan and nearly everywhere else.

This not only means that China has upwards of a half-billion tons of excess capacity that will crush prices and profits, but, more importantly,that the one-time steel demand for steel industry CapEx is over and done. And that means shipyards and mining equipment, too.

Nor is its own tail the only loss of market. Even more fantastic than steel has been the growth of China’s auto production capacity. In 1994, China produced about 1.4 million units of what were bare bones communist era cars and trucks. Last year is produced more than 23 million mostly western style vehicles or 16X more.

And, yes, that wasn’t the half of it. China has gone nuts building auto plants and distribution infrastructure. It is currently estimated to have upwards of 33 million units of vehicle production capacity. But demand has actually rolled over this year, and have been temporarily revived by government tax gimmicks that are simply pulling forward future sales.

The more important point, however, is that as the China credit Ponzi grinds to a halt, it will not be building new auto capacity for years to come. It is now drowning in excess capacity, and as prices and profits plunge in the years ahead the auto industry CapEx spigot will be slammed shut, too.

Needless to say, this not only means that consumption of structural steel and rebar for new auto plants will plunge. It also will result in a drastic reduction in demand for the sophisticated German machine tools and automation equipment.

Stated differently, the CapEx depression already underway in China, Australia, Brazil and much of the EM will ricochet across the global economy. Cheap credit and mispriced capital are truly the father of a thousand economic sins.

In fact, the cascade of downward adjustments from the global CapEx depression will penetrate deep into the global economy, creating unexpected victims as it goes along. One of those will be a double-hit to the iron ore industry and implicitly orders for the big yellow mining machines shown above.

During China’s massive boom it overwhelmingly consumed virgin iron ore because its one-time build-out of an industrial economy was not yet generating much scrap steel. But now as its vehicle fleet begins to age and excess capacity throughout if industrial and public infrastructure ages, atrophies or is actually dismantled under orders of its Beijing suzerains, it will soon be drowning in scrap steel.

That’s perhaps the reason that market prices for money and capital are such fundamental ingredient of true capitalist prosperity. It’s perhaps also the reason for what we have now is nothing of the kind.

Reprinted with permission from David Stockman’s Contra Corner.

The post It’s Different This Time appeared first on LewRockwell.

Leave a Reply