The Odds of a Global Food Crisis Are Rising

Given the current abundance of food globally, confidence in permanent food surpluses and low grain prices is high. Few worry that the present abundance of food could be temporary. But the global food supply is more fragile than we might think, despite historically low grain/agricultural commodity prices.

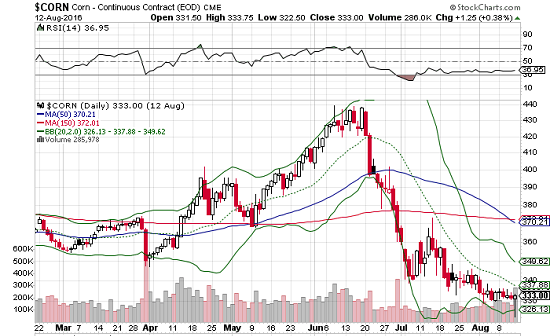

Both corn and wheat have plummeted in price due to current demand/supply:

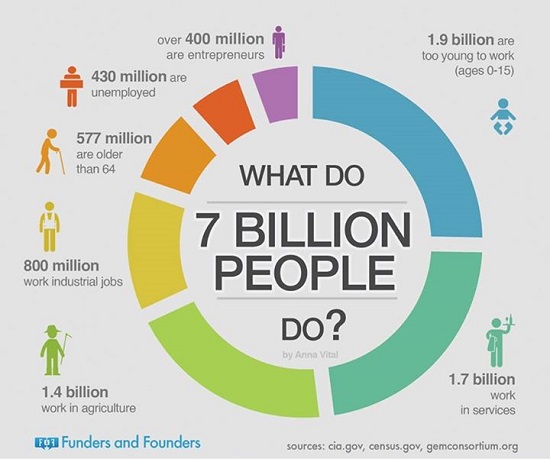

Let’s start with one salient fact: there are 7+ billion human mouths to feed nowplus hundreds of millions of animals that are being fed grain to supply humanity’s insatiable appetite for meat:

What few consumers grasp is that the global abundance of food depends on weather extremes remaining rare. If extremes of weather become commonplace, global food surpluses will turn into shortages.

In the larger context, the global food supply chain is a real-world system that cannot be “fixed” with financial gimmicks. No amount of money-printing will replace crops lost to weather extremes, replenish depleted fresh-water aquifers, magically rebuild top soil lost to erosion or repair the environmental ravages of industrial pollution.

In Globalization’s Few Winners and Many Losers (July 20, 2016), I discussed the fatal flaws in market price discovery: in the Tyranny of Price, risks and costs imposed by environmental degradation are ignored in price discovery, along with largely invisible declines in value, quantity and quality.

Longtime correspondent Bart D., who works in Australia’s agricultural sector, recently described the role extreme weather plays in reducing crop yields and food security:

“The tyranny of price not only results in a deluge of products of inferior quality that hurts us financially. The bigger issue in my mind is that we have created a global ‘landfill economy’ that is stripping the natural resource base to the bone and creating pollution on a scale that our increasingly resource constrained future economies will find difficult or impossible to ameliorate.

We can recover from economic damage caused by financial shenanigans relatively easily once the decision has been made to do so. But damage to the natural resource base that we all depend on may be impossible to overcome. That damage cannot be quickly fixed by tweaking legislation and financial systems.

Regarding the vulnerability of agricultural yields to increasingly common extremes of weather:

I think I can now see actual effects of climate change on the ground where I live. Recently we had both the coldest winter day (first frost I’ve seen in my 12 years living in my current home) and warmest winter day (practically a summer day) in the same week in mid-winter. This weirdness, if it continues (let alone gets worse), has an immense capacity to crimp food production.

Most people don’t appreciate that it takes six months to grow a wheat crop and only a single extreme weather day to wipe out a large part of its yield potential. In my part of the world, a single night of frost at the wrong time can reduce hundreds of thousands of acres from 2 ton yield per acre to just a few hundred pounds per acre. A few hot windy days can cut it in half. As can a week of wet weather during summer harvest. We are seeing an increase in all these types of events in the grain growing region where I live.”

The vulnerability of global food production to extremes of weather is a profound reality that few grasp. A single hard frost can decimate yields in a day or two just as effectively as drought can devastate crop that are not irrigated.

In effect, the global abundance of food depends on the rarity of weather extremes. If weather extremes become more common, it will follow like night follows day that agricultural yields will plummet accordingly.

Few people expect anything other than a permanent stable abundance of grains and other foodstuffs. The idea that multiple failures in multiple crops could make basic foods scarce is not even considered a possibility.

Returning to the Tyranny of Price: how accurately does the market price in the decline in food’s nutritional value as the soils are depleted? How accurately does the market price in the future health costs of polluted water and soil? How accurately does the market price the consequences of rapidly dropping water tables and the draining of aquifers? Does price reflect the danger of key glaciers that provide water for millions of people melting away?

The answer is the market ignores all these critical factors. They are not factored into the market price at all, because the market only prices in supply and demand in the present. Nothing else is counted or calculated.

While we’re discussing the potentially devastating consequences of weather extremes, let’s also consider urbanization/ suburbanization and the rapid aging of the world’s farmers. Prime agricultural land has been paved over for decades, and some day we may regret this staggering loss of deep soil to suburban sprawl.

The average age of farmers in Japan is 67, and over 58 in the US. The work is hard, risky and demands large investments of capital and time, and so relatively few young people are able or willing to become farmers. In rural China, an entire generation of over-60 people perform the physically punishing work of small-scale by-hand farming while their children work in the cities.

Where are the Future Farmers to Grow Our Food?

We take it for granted that somebody will do the heavy lifting of growing our food, regardless of the difficulties. But what happens when the generation of aging farmers retires en masse? Who will replace their expertise and experience?

The only way aging farmers will be replaced by young people is if prices for agricultural products rise to the point that they exceed the financial rewards of working in cities by a significant margin. When agriculture is the place to get rich, it will attract younger farmers and capital.

Let’s suppose extremes of weather decimate yields globally for a few years in a row. What happens to prices of basic foods? They skyrocket, of course, pricing out the poor. The poor then demand subsidized food, and fearful governments either supply the subsidized food or they risk outright rebellion from hungry desperate people.

In a real global food crisis, there won’t be enough to go around. Those nation-states with surpluses to sell will be able to dictate whatever terms they choose, as I discuss in The Ultimate Long Game: Autarky and Resilience.

The potential for a global food crisis is heightened by the confidence that such a crisis could not happen in the era of modern high-yield agriculture. But as Bart observes, a scarcity of food cannot be fixed by financial legerdemain.

The weather isn’t affected by our debates over the causes of global warming and weather extremes. Perhaps we should be focusing on making our fragile global food supply chain more resilient in an era of increasing weather extremes, and start pondering the cost of degraded/depleted soil and fresh water.

Maybe we should start thinking about who will replace the aging generation of farmers who will be physically unable to do the work in a few years.

Or we can wait until a “surprising and unexpected shortage” of food hits the human populace with full force.

This essay was drawn from Musings Report 33. The Musings Reports are emailed weekly to subscribers ($5/month) and major contributors ($50+ annually). The financial support of generous readers pays for the “free” blog posts and enables me to write books of marginal interest to the mainstream. Thank you, generous readers!

My new book is #5 on Kindle short reads -> politics and social science: Why Our Status Quo Failed and Is Beyond Reform ($3.95 Kindle ebook, $8.95 print edition)For more, please visit the book’s website.

Leave a Reply