Trump in Context

In what he represents, Donald Trump is not as unique as either his admirers or his despisers think.

How do we explain the Trump phenomenon? When he announced his candidacy for president, no one believed that he had a realistic chance to enter the White House. He was viewed as a joke candidate running an ego-driven campaign to promote his brand and his reality television show. He stunned everyone by defeating 16 opponents for the Republican presidential nomination—most of whom were respected, professional politicians. He did this despite increasing opposition and hysteria from the GOP establishment, Beltway conservative pundits, neoconservatives, the Bush family, Fox News, the mainstream media, Wall Street, and the Democratic Party. He became the first non-politician to be selected as a presidential nominee of a major party since General Eisenhower in 1952.

Many people—locally, nationally, and internationally—are shocked by, and fearful of, what Trump represents. How could this have happened? Trump is a singular person but his nomination as a non-politician is not unprecedented and he embodies some important political values. He can be placed in historical and ideological context.

Trump’s Appeal

Before getting to the context, however, we should spend a few minutes on Trump’s appeal. Initially, his candidacy was almost universally seen as a self-promoting stunt. He reportedly had to hire a crowd of actors to cheer for him when he came down the escalator at Trump Tower in New York City to announce. He is not qualified to be president. He is obviously crude and crass. If he is a Christian, his faith is childlike.

Physical Gold & Silver in your IRA. Get the Facts.

So what accounts for Trump’s success in the primaries—a close second-place finish in the Iowa caucuses, a smashing victory in the New Hampshire primary, and then important wins in contested states like South Carolina, Nevada, Georgia, Alabama, Virginia, Michigan, Florida, Illinois, Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Indiana? His national appeal was broad enough to chalk up victories in both Massachusetts and Mississippi, New York and North Carolina. By the time the primary season ended, Trump had set a new record for the number of raw votes received by a Republican: over 13 million. It was an astounding feat for someone who had never run for elective office before, who was a complete political amateur.

Trump accomplished this despite media ridicule and hostility, including an order from Rupert Murdoch to Roger Ailes of Fox News to take down Trump by having the moderators hammer him in the Fox debate of August 6, 2015 (“This has gone on long enough,” Murdoch told Ailes.) Yes, the television networks often covered his well-attended rallies live but they did this early on not because the TV executives and reporters were trying to help him into the White House but because he was good for the corporate bottom line. He attracted ratings and ratings translate into profits. This self-interested national public platform eventually gave way to open opposition by almost every mainstream media outlet.

Such media vitriol had not been seen since Barry Goldwater ran for president in 1964. Trump was routinely described as racist, xenophobic, anti-Semitic, misogynistic, obnoxious, stupid, violent, and insane. He was compared to Hitler. Guilt-by-association charges linked him to the Ku Klux Klan, the Mafia, Vladimir Putin, and Saddam Hussein. Supposedly objective newswire companies such as the Associated Press disseminated almost nothing except snarky, inaccurate, and out-of-context stories on a daily basis. They did this with a straight face, as “fact checkers” worked overtime pretending to debunk almost everything Trump was saying. Of course, the corporate press did not explain the threat that a Trump presidency would pose to themselves and the power elite status quo of which they were a part.

Populism and nationalism are not only upsetting on a personal level to those who wield power and profits under the status quo; they are also a threat to their jobs and income. Trillions of dollars are stake in such sacrosanct, bipartisan pillars of established statecraft such as Wall Street, the Federal Reserve, open borders for cheap labor, managed trade pacts like NAFTA and TPP, the Pax Americana global empire, NATO, perpetual war in the Middle East, and the federal government’s special relationships with Israel and Saudi Arabia. One nutty celebrity businessman too rich to be controlled cannot be allowed to stand in the way of such important and beneficial things. So all stops have been pulled out. To the point where Donald Trump—who has been well known for decades to Americans—has been demonized.

Obviously, Trump’s egomaniacal persona and choleric temperament have been off-putting to many voters. While the media have capitalized on every misstep in a way they have never done with members of the Bush and Clinton families—whom they generally like and with whom they can do business—the media have not caused these missteps. Most are self-inflicted. They reflect both Trump’s inexperience in electoral politics and penchant for emotional, honest outbursts. In many ways, he is ill-suited for high public office in the 21st century. He has clear deficiencies in temperament and experience. (Although, it must be added, many people appreciate his unfiltered speaking, unambiguous masculinity, relatable earthiness, business success, and celebrity status.) He has a poor character in the eyes of both religious moralists and political-correctness acolytes. If temperament, experience, and character are a mixed bag at best, it means that Trump’s strongest suit is policy.

What is the main reason so many voters—not only Republicans but also Independents and Democrats—have flocked to Donald Trump? By January 2016, he was seen as the only genuine anti-establishment figure in the Republican primaries who had a chance of winning the nomination. Rand Paul ran a poor campaign and blew his opportunity. Ben Carson was likeable but an underwhelming speaker. Ted Cruz said the right things to each audience he addressed but his televangelistic, unctuous speaking style raised doubts about his sincerity. Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio represented the latest incarnations of the failed Bush-McCain-Romney status quo. Even the hyperventilating opposition of institutions like George Will, David Brooks, Charles Krauthammer, Bill Kristol, National Review, and the DC-based Religious Right was not persuasive.

Instinctively, if not intellectually, Trump supporters viewed the conservative Never-Trump crowd as hucksters who have made billions over the decades from sincere grassroots Republicans while delivering nothing in terms of good public policy from their offices in suburban Virginia. It all seen as a self-serving charade. A crooked game designed to turn out votes for pragmatists like Dick Cheney, John Boehner, and Mitch McConnell, who have never genuinely cared about conservative principles (economic, social, or constitutional). Trump was burning the whole dishonest GOP power structure to the ground. For millions of cynical and disengaged voters, this has been exhilarating. The many failures of the George W. Bush years were never acknowledged, let alone apologized for, by the Republican Party in 2008 and 2012. In one sense, Trump is the “Payment Due” notice for this inability to be honest and conservative.

Many Trump supporters probably worry about whether he will follow through on his promises and conduct himself in a way that will not bring discredit upon himself and our country if he becomes president. At the same time, he represents the first real opportunity in decades to change the direction of the country. Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton have both promised more of the same. Most Americans, being populist and nationalist, do not like a corporate-dominated political system, economic globalism, and unnecessary wars and foreign meddling. Sincere or not—and evidence suggests that he is sincere—Trump promises a change.

Historical Context

Although Donald J. Trump is extraordinary as a presidential nominee in 2016, there are historical antecedents. They fall into three categories: personality (choleric), background (business), and ideology (populism). By personality, I mean a choleric temperament characterized by being practical, strong, productive, willful, bossy, combative, and irritable (among other things). By background, I mean a business leader—specifically an entrepreneur who became wealthy by building a large company. By ideology, I mean an embrace of populism, which supports the rights, aspirations, and power of the people (i.e., democracy).

Analogous examples in history of presidential contenders with a choleric personality include President Andrew Jackson, Senator Hiram Johnson, President Harry Truman, and Texas billionaire Ross Perot. Jackson was viewed by many of his more respectable contemporaries as unqualified for the White House given his fiery temper and violent past. Johnson, the California governor who was Theodore Roosevelt’s Bull Moose running mate in 1912 and went on to become a giant of the U.S. Senate and two-time GOP presidential candidate, was strong and stubborn. Sam Francis once called Truman “perhaps about as close an imitation of Il Duce [Mussolini] as this country has ever produced.” Perot had a charming side to him as an independent candidate but was also known to be prickly and argumentative.

Candidates with a business background who could be thought of as forerunners of Trump include newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, automobile pioneer Henry Ford, mining engineer Herbert Hoover, utilities executive Wendell Willkie, Texas wheeler-dealer John Connally, publisher Steve Forbes, and pizza executive Herman Cain. Hearst was a leading contender for the Democratic nomination in 1904 but his wealth and private life offended many Democrats who shared his populist views, including William Jennings Bryan. Ford twice tested the presidential waters and twice won the Michigan primary—on the Republican side in 1916 and the Democratic side in 1924. Hoover, who had become a multimillionaire by the age of 40 with investments throughout the world, was touted for president in 1920 within the Democratic and Republican parties (and served as secretary of Commerce prior to becoming president). Unlike Hearst and Hoover, the next three forerunners did not build a great business empire of their own. Willkie, who had been a Democrat before capturing the Republican nomination in 1940, moved from being a corporate attorney to the president of a New York-based utility company. Connally had been an LBJ protégé, a corporate lawyer, federal department secretary, and Democratic governor of Texas before running a business-friendly campaign for the 1980 Republican nomination. Forbes, who managed his family’s self-titled financial magazine, ran for the 1996 and 2000 Republican nominations, incorporating elements of both libertarianism and social conservatism. Cain, a Pillsbury and Burger King executive before becoming CEO of Godfather’s Pizza, moved into politics after retiring from business and made an attempt at the 2012 Republican nomination.

In addition to candidates with a business background, we can consider the broader category of contenders who were not professional politicians before seeking the presidency. Some had non-business backgrounds. By the mid-1800s, nominating conventions were choosing one national standard bearer to represent each major political party. If we set aside potential nominees and concentrate on actual nominees, there were 12 such men chosen by their parties to compete in the general election between 1848 and 2008:

1848 – Gen. Zachary Taylor (W)

1852 – Gen. Winfield Scott (W)

1856 – Maj. (and pioneer) John C. Frémont (R)

1864 – Gen. George McClellan (D)

1868 – Gen. Ulysses Grant (R)

1872 – editor Horace Greeley (D)

1880 – Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock (D)

1904 – Judge Alton Parker (D)

1908 – Judge/Sec. William Howard Taft (R)

1928 – businessman/Sec. Herbert Hoover (R)

1940 – businessman Wendell Willkie (R)

1952 – Gen. Dwight Eisenhower (R)

Of these 12, two served in Congress for less than a year prior to seeking the presidency—Frémont was briefly a member of the U.S. Senate (D-CA) and Greeley was briefly a member of the U.S. House (W-NY)—but neither was known primarily as a politician. Seven of the 12 were military officers. Six of those seven were generals (the one exception, Frémont, later became a general during the Civil War). The tradition of choosing a non-politician as a presidential nominee was most popular in the mid-to-late 1800s. There were seven of these nominees during a 32-year period. It was a more rare circumstance in the twentieth century, with all such examples taking place before 1960. Over the years, there have been a few presidential nominees with relatively little and minor experience in elective office before being nominated—notably William Jennings Bryan (1896) and John W. Davis (1924). Both served only in the U.S. House (Bryan for four years; Davis for two).

Not surprisingly, populism is popular with the people who elect candidates to public office. This being the case, and politicians often wanting to tell voters what they want to hear, most candidates pose as populists of some sort—economic or cultural—whether they are actual populists or not. An insincere “populist,” who intends to use the people as a stepping stone to personal power, is more accurately labeled a demagogue. There is also a populism-of-style that sometimes has little correlation with populism as an ideology. Examples of candidates who have had a folksy, down-to-earth personality but have filled their administrations with plutocratic appointees and policies include Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush.

Given the importance of public policy of a candidate’s ideology, I am seeking to identify genuine populists as Trump antecedents. It is a judgment call since honesty and motivation are often difficult to discern with confidence. But politicians have a track record when it comes to executive actions, voting records, campaign contributions, and institutional affiliations. I use these to identify political populists since the nineteenth century. Examples of Trump-like candidates who have favored popular sovereignty over elite rule include President Andrew Jackson, three-time nominee William Jennings Bryan, William Randolph Hearst, Henry Ford, Hiram Johnson, Senator Huey Long, Senator Robert Taft, Senator Barry Goldwater, Senator George McGovern, Governor George Wallace, Governor Ronald Reagan, Governor Jerry Brown, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Rev. Pat Robertson, commentator Pat Buchanan, Ross Perot, attorney Ralph Nader, Congressman Ron Paul, Congressman Dennis Kucinich, Senator Mike Gravel, and Senator Bernie Sanders.

Despite his wealth, Pres. Jackson was loved by many of the common people and his name is attached by historians to the growing democratization of the country. He is also famous for having successfully killed the aristocratic Second Bank of the United States. Nationalism—as opposed to internationalism, globalism, and imperialism—is often linked to populism. An “America First” type of patriotism is popular with average Americans. Not as a banner under which to conquer other countries and intervene in their internal affairs but rather as a means of loving our own country and defending it. In modern political discourse, Gen. Jackson’s name is also attached to a type of nationalism that includes military might but not in an imperialistic, supposedly “do-gooder” way in far-away places (e.g., going “abroad in search of monsters to destroy,” to quote Jackson’s opponent John Quincy Adams).

As someone in the Jefferson-Jackson tradition, with an added infusion of evangelical Christianity, Bryan was the leader of the populist wing of the Democratic Party from 1896 to 1912. More pacifist than Jackson, Bryan opposed the proposed League to Enforce Peace in 1916-17 because he thought it would pull the nation into unnecessary wars (“America first!…Beware of Entangling Alliances,” he wrote). Later, he supported the League of Nations but unsuccessfully pressed for sovereignty-protecting reservations (amendments).

Hearst was a populist and nationalist. He supported Bryan for president in 1896 and 1900. In 1904, his own platform was radically left-wing by respectable standards of the day. During his unsuccessful campaigns for president, mayor of New York City, and governor of New York state, Hearst was backed by many urban workers. He was an “isolationist” in foreign policy in the sense of wanting to follow the traditional Washington-Jefferson advice of steering clear of foreign political/military alliances. Hearst opposed U.S. involvement in World War I, the League of Nations, the World Court, and World War II. Although viewed as more conservative in his later years, he continued to support populist/nationalist candidates in both parties during the 1920s.

Like Hearst, Ford built a fortune that allowed him to have independence from Wall Street. Ford thought of himself as a friend to the common man, distrusted New York banks, and attempted to keep the U.S. out of World War I. His anti-Semitism, however, repelled many Democrats in the early 1920s, including W.J. Bryan.

Johnson was a populist progressive within the GOP as governor and senator of California from the 1910s through the 1940s. He voted against the League of Nations. His 1920 campaign for the presidential nomination used the slogan “America First.” As ranking Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he resisted U.S. entry into World War II and was planning to vote against the United Nations charter in 1945 (dying, he was too sick to vote).

As governor and senator of Louisiana, Long fought New York-based monopolies, including Standard Oil. Despite his autocratic style and questionable ethics, he was apparently a sincere populist. Viewed with alarm by the plutocratic press as a radical leftist, he was planning to challenge FDR for the 1936 Democratic nomination when he was cut down by an assassin. He had publicly stated that his choice for secretary of War would be Gen. Smedley Butler, highly-decorated veteran and author of the anti-war book War is a Racket.

Taft was a populist opponent of Wall Street despite his own background of privilege as the son of a president. His foreign policy was one of America First nationalism. He opposed U.S. entry into World War II, was skeptical of the Marshall Plan, opposed the creation of NATO, and criticized the imperialism and militarism of the Cold War despite being anti-communist.

Goldwater was more hawkish than Taft but he was a nationalist supporter of the Cold War, not an internationalist in the bipartisan Truman-Rockefeller tradition. He was a strong advocate of free-enterprise capitalism but his 1964 candidacy was supported by national-focused businessmen, not by the larger transnational corporations. Like Taft, Goldwater was feared and detested by Wall Street Republicans. He represented Middle America while Rockefeller-Romney-Scranton (R) and Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson (D) were the electoral favorites of corporate America. Goldwater was arguably the last anti-establishment presidential nominee of the Republican Party until Trump over 50 years later.

Wallace is tainted (understandably so) by the racism associated with his defense of segregation in Alabama in the early 1960s. His evolution as a national figure during his four consecutive presidential campaigns, from 1964 to 1976, increasingly moved his emphasis from racism to populism. This was not simply a cynical attempt to expand his base. He was in the tradition of Jefferson-Jackson-Bryan southern populists who were both race-baiters and genuine populists (e.g., Benjamin Tillman, James Vardaman, Theodore Bilbo). While he was one of the three top contenders for the 1972 Democratic nomination, he was shot by a would-be assassin. Unlike Long, Wallace lived. Gov. Wallace failed in the 1976 primaries but opened the door for a party-transcendent populist coalition led by Gov. Reagan.

In 1972, McGovern became the first anti-establishment presidential nominee of the Democratic Party since Bryan in 1908. His campaign slogan “Come Home, America,” reflected his opposition to the Vietnam War and imperial overseas entanglements in general. The radical implications of populism and nationalism were sometimes compromised by McGovern’s tendency to be a bleeding-heart, big-government liberal Democrat. Still, his abandonment in the general election by the party’s power brokers and traditional funders were a sign that his politics were unacceptable to Wall Street and the military-industrial complex.

As a former Hollywood actor, Reagan was not a professional politician of many years. As California governor, however, he did lead the nation’s largest state for eight years and he made three attempts at the White House before entering it. These things set him apart from Trump. He was also an ideological hero for the conservative movement. He represented the populist wing of the Republican Party by 1976 when he challenged the Ford-Rockefeller administration in the primaries. He was opposed by Wall Street and the establishment wing of the GOP. Locally, wealthy country-club Republicans sided with Ford against Reagan, just as most had done with Rockefeller against Goldwater (1964) and with Eisenhower against Taft (1952). In foreign policy, Reagan was in the Goldwater mold of well-armed nationalism against détente-minded internationalism. The mainstream media mocked and castigated Reagan as stupid, extreme, and dangerous. Some of that criticism carried over to his successful 1980 campaign, but when he chose George H.W. Bush as his running mate, he apparently made his peace with the establishment. Generally speaking, the Reagan presidency was filled with Nixon-Ford-Bush Republicans in the top positions and its policies were more corporate-friendly than populist.

John Connally was not a populist but he did have a nationalist message in 1980 and when he lost the South Carolina primary to Governor Reagan, he supported the Californian over the more-global-minded George H.W. Bush in the Texas primary.

Brown—the once and present California governor (young and very old)—ran for president in three different decades. His first bid, in 1976, was tentative and late. His second, in 1980, was interesting in its appeal but fell flat when faced with stronger opponents (Pres. Carter and Sen. Kennedy). His third, in 1992, was the most successful of all. He tapped into the anti-establishment sentiment of that year, along with Buchanan and Perot, and his overt populism and peace-minded nationalism had a transcendent appeal across partisan and ideological lines. Brown condemned the Persian Gulf War and urged rejection of NAFTA. He garnered millions of votes in the primaries and continued to challenge Gov. Clinton at the convention. He refused to support the nominee in the fall. He briefly left the Democratic Party during the Clinton years, in the mid-1990s, denouncing it as a tool of Wall Street and other corporate interests. After becoming mayor of Oakland, state attorney general, and governor once again, Brown is now just another conventional liberal Democrat.

Rev. Jackson, like Trump, was not a politician when he first sought the presidency. He was a minister, but, more importantly, he was a civil rights leader. In 1984, he ran as the first African American to mount a serious bid for the Democratic nomination. He received 3.5 million votes and carried several states. Four years later, he doubled his popular support as he ran a populist campaign that pulled in a substantial number of white voters to supplement his black base of support. He won a half-dozen southern states and even some northern states, including Michigan and Alaska. Jackson’s 1988 primary vote was nearly a third of the electorate and he was the runner-up at the convention. It was an amazing accomplishment for a non-politician. In 1993, Jackson was part of what the Wall Street Journal disparagingly called “the Halloween Coalition” of populists who united, despite party and ideology differences, to try to stop NAFTA (other members: Brown, Buchanan, Perot, and Nader . . . and, less publicized at the time, Trump).

Nader, a renowned consumer advocate, and progressive activist, was a candidate for president in four consecutive elections—twice with the Green Party and twice as an independent. Possessing an ideology of transcendent populism, Nader has tried to unite the grassroots Left and grassroots Right against the plutocratic Center. As a candidate, he had limited success in reaching beyond his base of true-believer liberals. Many Democrats began to hate him because they (wrongly) blamed him for causing the loss of Gore in 2000 (a year in which Nader garnered 3 million votes). He is also not considered trendy by 21st-century progressives because he eschews identity politics and obsession with sexual-centered cultural issues in favor of a unified coalition of the common people. Ironically, the populist Nader came out with a book, in 2009, called Only the Super-Rich Can Save Us! Written in utopian fiction style, the book did not include Trump among the hoped-for helpful billionaires.

Kucinich, Gravel, and Sanders each waged unsuccessful campaigns for the Democratic nomination during the 2004-2016 period. The first two were not nearly as popular as Jackson or Brown at their peaks (1988 and 1992, respectively). Sanders, on the other hand, exceeded their success even though he, too, fell short by the end of the primary season. All three denounced plutocratic politics. Kucinich added a New Age spirituality vibe, including vegetarianism. Gravel emphasized direct democracy. Just as Brown had done with Bill Clinton, Sanders criticized Hillary Clinton for her cozy relationship with Wall Street. Kucinich and Gravel were not nationalists but they were internationalists à la John Lennon (not Henry Kissinger/Madeleine Albright/neoconservatives). Sanders was more tentative in his foreign policy pronouncements but he was an opponent of the Iraq War (unlike the Clintons). Strange as it seems to conventional wisdom, there is cross-over support for both Sanders and Trump (for backers of each who do not prioritize social issues). Populism is the explanation.

Robertson, Buchanan, Perot, and Paul each represent a populist/nationalist movement within conservatism and the Republican Party that culminated in the nomination of Trump in 2016. For this reason, they will be dealt with in greater detail.

Ideological Context

Many were mystified when Donald Trump drew huge crowds, rose in the polls, and won primary contests. He did this within the context of the Republican Party, despite having a record of loose partisan affiliation, at best. In the recent past, he had complained about President Bush and contributed money to politicians of both parties, including Hillary Clinton and Nancy Pelosi. He was not part of the DC-based conservative movement. He was not known as a social conservative.

Yet Trump’s base of support consisted of conservative rank-and-file Republicans, not pragmatic leaders and donors associated with the GOP establishment. He was backed in the primaries by many Tea Party and evangelical Protestant Republicans despite incessant denunciations by Senator Ted Cruz, who declared that Trump was not a real conservative but rather a liberal Democrat at heart. Republicans were warned that Trump had “New York values,” not the middle-American family values of constitutional conservatism and the Religious Right.

Despite dismissals of Trump’s purity and ideology by the Cruz campaign, National Review magazine, Fox News, foreign policy neoconservatives, and George W. Bush operatives such as Karl Rove, Trump resonated with millions of grassroots conservatives and his appeal grew over time. Why? Because Trump is a conservative. Conservatism is not monolithic or one-dimensional. There are different aspects to the ideology, worldview, and movement known as conservatism.

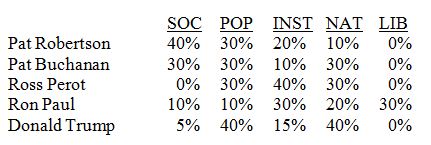

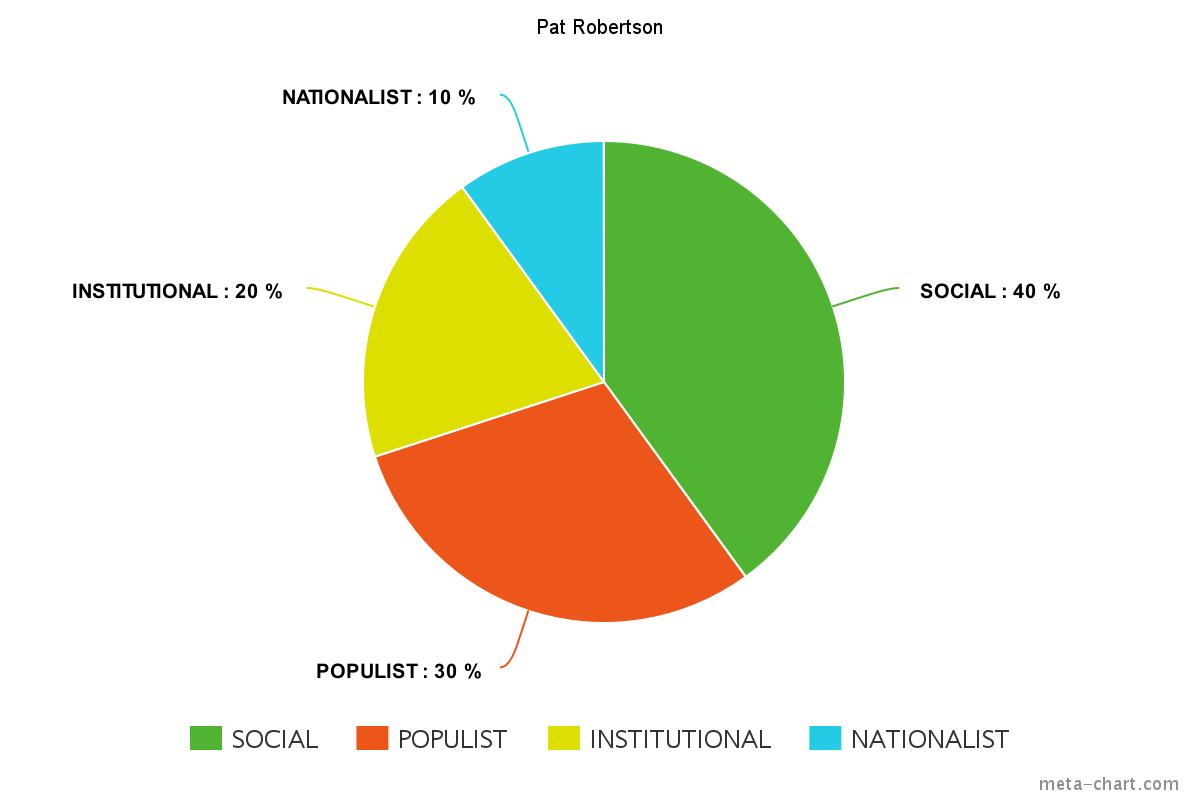

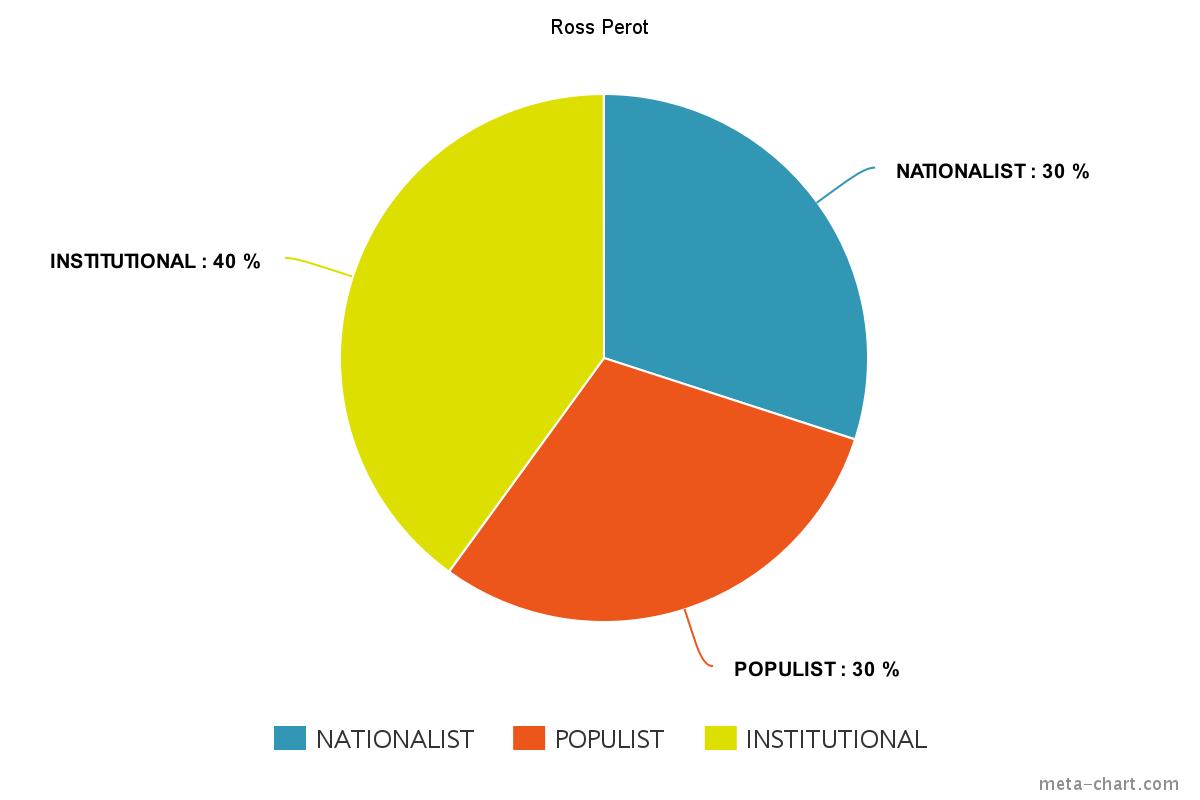

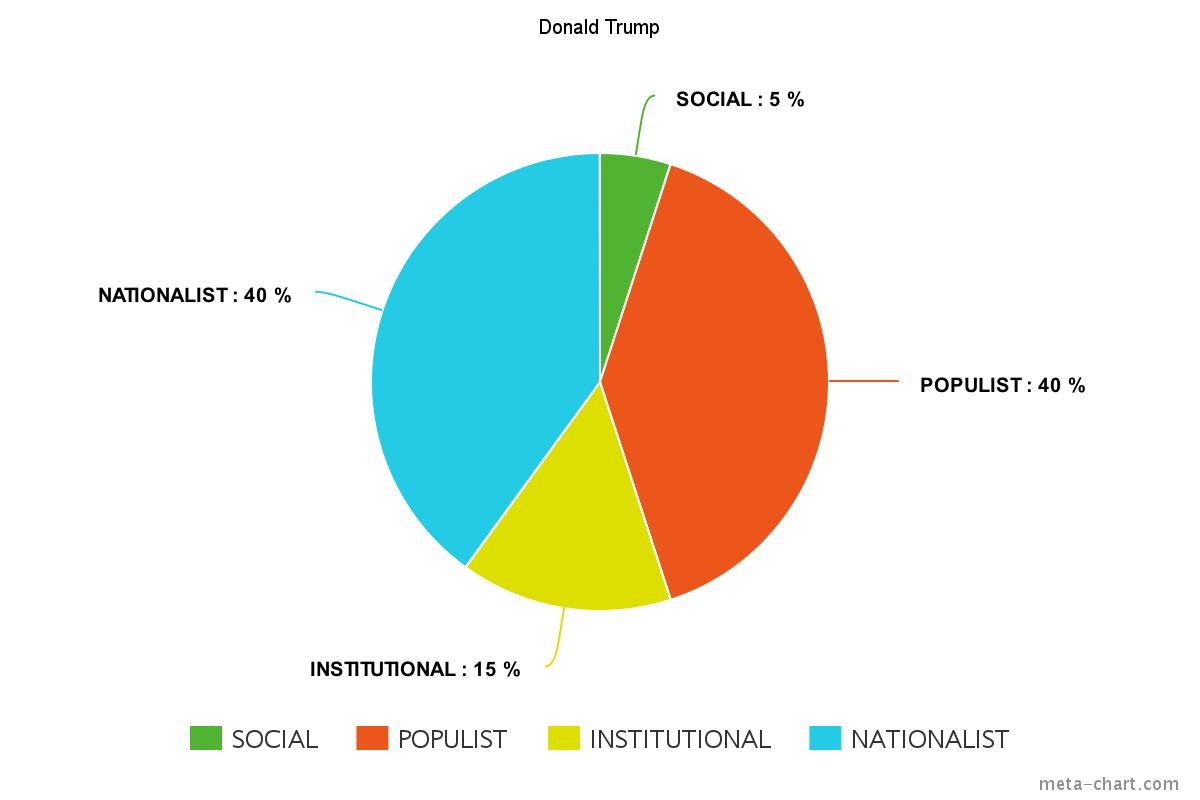

There are five varieties of modern American conservatism, in its most genuine and traditional sense: Social, Populist, Institutional, Nationalist, and Libertarian.

Varieties of Conservatism

SOC = Social (pro-Christianity, pro-social-morality, pro-traditional-marriage, anti-abortion, anti-sexual-hedonism)

POP = Populist (pro-democracy, anti-elitist, anti-Wall Street)

INST = Institutional (pro-Constitution, pro-limited-gov’t, pro-fiscal-restraint, anti-deficit, anti-progressive-pragmatism)

NAT = Nationalist (pro-Am-First, pro-fair-trade, anti-globalization, anti-world-policeman, anti-UN/NATO/NWO)

LIB = Libertarian (pro-freedom, pro-individualism, pro-natural-rights, anti-statism)

Despite his unusual business and television background, crude personality, and instinctive (rather than intellectual) politics, Donald Trump is in an identifiable stream of populism/nationalism that was exemplified on the national stage by presidential candidates Pat Robertson, Pat Buchanan, Ross Perot, and Ron Paul during the 1988-2012 period. Each of these candidates have been standard bearers of the varieties of conservatism in varying proportions. All five have been Populist, Institutional, and Nationalist conservatives.

While his own lifestyle was conservative, Ross Perot was more of a social liberal on issues like abortion and did not articulate positions congenial to Social conservatives. Trump had a similar background but claimed to be pro-life by 2011, when he was flirting with a bid for the GOP presidential nomination. Four years later, he talked some about the abortion issue and his Christian faith as he courted “the evangelicals,” but holding up his church confirmation Bible and talking about “Two Corinthians” at rallies were widely seen as inauthentic, amateurish, and risible. Given the presence of evangelical favorites Ted Cruz, Ben Carson, Rick Santorum, and Mike Huckabee in the GOP field, Trump’s small-but-determined effort to court conservative Christians would have been a hard sell in the early days of the campaign even if it had been done more smoothly.

Of the five candidates, only Ron Paul had a significant Libertarian component during his three campaigns for the presidency. However, the nationalism of Buchanan and Perot attracted some libertarians, including Murray Rothbard, because application of the non-aggression principle brought Libertarian and Nationalist conservatives together on foreign policy, in opposition to war-minded internationalists. Although Trump had almost no emphasis on individual freedom during the primary season, there was a trace of libertarianism in his frequent denunciations of political correctness (a form of cultural totalitarianism) and his free-wheeling, shoot-from-the-hip personal style.

Trump’s varieties-of-conservatism proportions are most closely paralleled by three-time presidential candidate Pat Buchanan. Perot is less close, with Robertson and Paul being even further removed, although in the same stream.

Recognizing ideological kinship, Buchanan supported Trump’s candidacy through his syndicated newspaper column, beginning in the Fall of 2015. He never wavered in his Trump enthusiasm through the primary, convention, and general-election seasons. Trump praised Robertson when he appeared at Regent University in February 2016 and the founder of the school reciprocated. Retired from politics, Perot has not publicly commented on Trump. Paul supported his son, Senator Rand Paul, for the GOP nomination in 2015 and early 2016, and has been critical of Trump’s lack of emphasis on liberty and the Constitution, despite convergences on some specific issues. Because of her peace-minded foreign policy consistency, Jill Stein of the Green Party has received more plaudits from Paul than has Trump in the Fall of 2016.

For his part, Trump made a point of praising Rand Paul’s father during a debate, despite personal acrimony between the two 2016 candidates. In August 2011, Trump tweeted that Ron Ron Paul is right that we are wasting trillions of dollars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Ron Paul is right that we are wasting trillions of dollars in Iraq and Afghanistan.Paul was right about the U.S. “wasting trillions of dollars” on the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and later used Twitter to criticize the media for ignoring Congressman Paul because he had “some serious ideas which deserve serious consideration.” Trump toyed with a run for the presidential nomination of the Reform Party, founded by Perot, in 1999. Ironically, his would-be opponent was Buchanan, who had left the Republican Party. Trump did not end up running, despite encouragement from Governor Jesse Ventura, but the flirtation is evidence of his maverick bona fides.

Despite Trump’s emphasis on populism and nationalism in 2015-16, mostly to the exclusion of other conservative themes, he was not a complete stranger to the conservative movement. He and his father, Fred Trump, were present at Governor Ronald Reagan’s announcement for the presidency in 1979 and they donated space for his Manhattan campaign office. Trump’s support for Reagan’s 1980 nomination is significant because the northeastern GOP establishment detested Reagan, instead favoring the more-liberal, more-pragmatic Howard Baker and George H.W. Bush.

In 1987, Trump took out a full-page ad in the New York Times criticizing the economic and foreign policies of President Reagan because they were insufficiently nationalistic. He attended the Republican National Convention in August 1988. Interviewed on CNN by Larry King, Trump twice rejected attempts to classify him as a northeastern liberal elitist. He was asked, “[You are] kind of a Rockefeller-Chase Manhattan Republican?” Trump replied, “I never thought of it in those terms.” King followed up with essentially the same question: “Are you a Bush Republican?” Trump: “No. I think I’m really . . . The people I do best with are the people who drive the taxis. You know, wealthy people don’t like me because I’m competing against them all the time and they don’t like me. And I like to win. The fact is, I go down the streets of New York and the people that really like me are the taxi drivers and the workers.” This is Populist conservatism. Obviously, it foreshadowed the campaign he would run three decades later.

If Donald Trump were not a credible conservative of some sort, his quest for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination would not have been supported—openly or tacitly—by true-blue conservatives such as Pat Buchanan, Phyllis Schlafly, Ann Coulter, Matt Drudge, Roger Stone, Robert Jeffress, Jerry Falwell Jr., Sarah Palin, Jeff Sessions, Virgil Goode, Ben Carson, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, David Stockman, Jeffrey Lord, Doug Wead, Steve Bannon, and Laura Ingraham, plus libertarians Lew Rockwell, Justin Raimondo, Walter Block, Ralph Raico, and Wayne Allen Root. Buchanan and Schlafly had unimpeachable conservative credentials as Goldwater-Reagan Republicans (the former was also a Taft backer in the key 1952 contest).No matter how the presidential election turns out on November 8, the Trump phenomenon—more a movement than a man—is unlikely to disappear within the party or the nation any time soon. Partly because of Trump’s unique strengths (and weaknesses); partly because he is the latest manifestation of long-standing historical and ideological traditions.

A version of this article was presented at the Front Porch Republic annual conference, on October 8, 2016, at the University of Notre Dame. Text, tables, and charts © Jeffrey L. Taylor, 2016.

The post Trump in Context appeared first on LewRockwell.

Leave a Reply