Uncle Sam (and the Taxman)

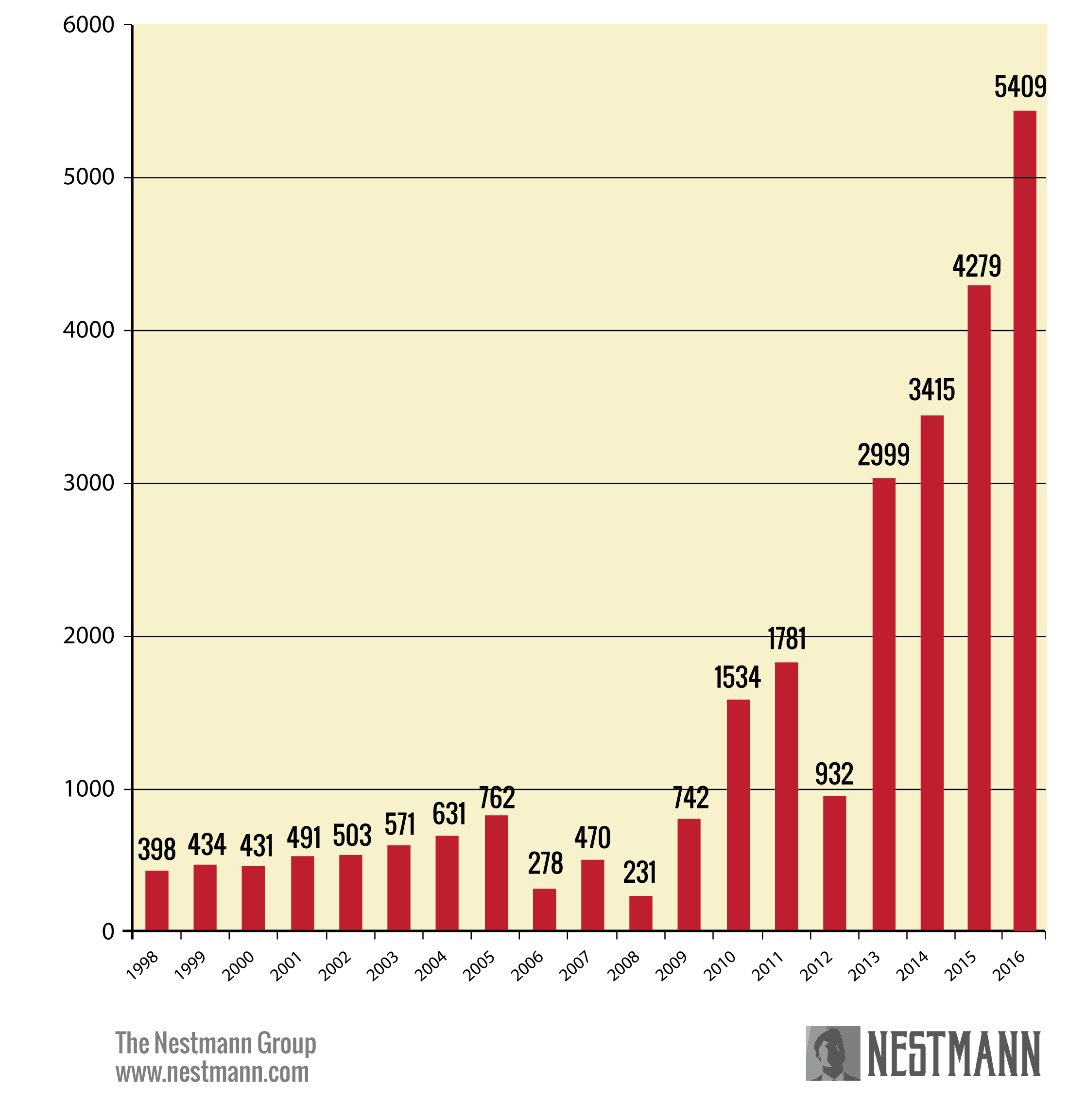

2016 was another record-breaking year for the number of US citizens and its long-term residents expatriating, giving up their US citizenship and passport or green card.

According to a February 9 announcement in the Federal Register, 2,364 expatriated in the fourth quarter of 2016, bringing the tally for last year to 5,409. That’s a 26% increase over 2015. It’s more than 13 times as high as it was less than two decades ago, as this chart reveals.

Myths, Misunderstandings and Outright lies about owning Gold. Are you at risk?

As high as these numbers are, I think they’re only the tip of the iceberg. That’s because of the way that the numbers published in the Federal Register are counted. Only those who formally notify the IRS that they’ve expatriated by filing Form 8854 – “Initial and Annual Expatriation Statement” – are counted.

You’re supposed to file this form if you expatriate, but many former US citizens and green card holders don’t bother. Why not? I think it’s because the form requires that you certify whether or not you have been tax-compliant for the preceding five years. There are millions of Americans – especially those living outside the US – who aren’t.

The numbers also don’t jibe with some older reports I’ve compiled.

- The South Korean media reported that 2,158 of its citizens gave up US citizenship or green cards in 2011. In other words, more people expatriated from a single country in 2011 than appeared on the official IRS list for the entire world for that year (1,781).

- The Swiss media reported that in the first nine months of 2012, 411 individuals expatriated at the US embassy in Bern, Switzerland. This would mean that Switzerland accounted for over 40% of the total expatriations in 2012 (932).

- Numerous public figures never appear on the official IRS list. They include Ukraine’s former first lady, Kateryna Yushchenko (2007); Jamaican politicians, Daryl Vaz (2008), Michael Stern (2009), and Danville Walker (2011); Hong Kong actors, Jaycee Chan (2009) and Erica Yuen (2012); and Korean actor, Yoo Gun (2011), among other examples.

For all these reasons, I think it’s logical to assume that the actual number of Americans expatriating could be as much as five to 10 times the statistics published in the Federal Register. In other words, perhaps as many as 50,000 annually.

Expatriating means giving up your right to live and work in the US. If you’re a former US citizen, it means surrendering your US passport – one of the world’s best travel documents.

So why bother? A clue comes from the fact that, at least in our own experience, the overwhelming number of expatriating Americans already live outside the US. There are more than 9 million Americans in this category.

The US is one of only two countries that impose income tax on its citizens on their worldwide income if they live in another country. Eritrea, a totalitarian dictatorship, is the other one. Complying with US tax rules is hard enough if you’re living in the US. But if you’re living in another country, you must now file two sets of tax forms each year.

Plus, laws like the infamous Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) have made it difficult for Americans living abroad to carry on the most basic financial and business relationships in their adopted countries. FATCA, for instance, forces foreign financial institutions to follow US tax and reporting rules with respect to their US clients. If these institutions fail to do so, they face a 30% withholding tax on many types of US source income and other capital transfers.

In many cases, it’s easier to “fire” US clients than deal with this risk. As a result, Americans living abroad report bank accounts being closed, mortgages called in, and insurance policies canceled. One client’s employer told him he’d be fired unless he gave up US citizenship within 30 days.

It’s also nearly impossible for an American living abroad to enjoy a normal retirement in their adopted country. That’s because with only a few exceptions, the IRS considers the buildup in value in a non-US retirement plan to be taxable.

And don’t forget that if you owe the IRS more than $50,000 in back taxes, the State Department can confiscate your passport.

The costs of expatriating, though, are steep. US citizens wishing to expatriate must pay a consular fee of $2,350. That’s the highest fee imposed by any country.

If you’re wealthy, expatriation can also lead to some unpleasant tax consequences. A 2008 amendment to the Tax Code imposes an “exit tax” on wealthy expatriates. It’s based on a legal fiction, as if you sold all of your worldwide property at its fair market value on the day before you expatriate. Tax on the fictional gain is due at the time your tax return is due for the year of expatriation.

The tax applies only to “covered expatriates.” You’re in this category if you:

- Have a global net worth exceeding $2 million; and/or

- Have an average annual net income tax liability for the five preceding tax years before the date of the loss of US citizenship or residence exceeding $162,000 (2017, adjusted annually for inflation); and/or

- Fail to certify under penalty of perjury on Form 8854 that you have complied with all federal tax obligations for the five years preceding expatriation.

No exit tax is due on the first $699,000 of unrealized gains (2017, adjusted annually).

The 2008 amendment also results in a covered expatriate’s IRA being considered as having been closed (with taxes due) and deemed termination of similar schemes in other countries. So in addition to paying capital gains tax on imaginary capital gains, you’ll pay income tax on imaginary income. And there’s no assurance that when you actually realize the income, the country you’re living in won’t impose tax a second time.

Also, as a covered expatriate, any gifts you make to a US citizen or permanent resident exceeding $14,000 annually are subject to a tax of 40% (or the highest estate tax rate currently in effect). The recipient of the gift must report it and pay the tax.

Careful planning can deal with some of these issues. Especially if you’re a covered expatriate, be certain to consult with qualified professionals before you sign away your citizenship or green card.

But it’s the final cost that’s the bitterest one: possible permanent exclusion from the US.

In 1996, Congress enacted a law called the “Reed Amendment,” which gave the attorney general the discretion to deny entry into the United States to any former US citizen who renounced US citizenship in order to avoid US taxation. While the amendment was criticized for violating US treaties and possibly the Constitution, immigration officials have unofficially used it to justify visa and re-entry denials to expatriated Americans.

Then in 2012, legislation to retroactively punish wealthy expatriates was introduced. The “Expatriation Prevention by Abolishing Tax-Related Incentives for Offshore Tenancy Act” (or Ex-PATRIOT Act) would have punished covered expatriates by forbidding them from ever reentering the United States. They would have also faced a 30% tax on future gains from US investments. Both provisions would have been retroactive for the 10-year period prior to enactment of the statute. The only way to avoid this result would be to prove that their expatriation didn’t result in a substantial reduction in their tax burden.

The Ex-PATRIOT Act didn’t become law in 2012, but it was reintroduced it in 2013. It didn’t pass then either. But I think the Trump administration could use this provision as a bargaining chip to garner political support for immigration reforms he can’t achieve via executive order.

Expatriation is a radical step, and as many as 50,000 Americans annually could be taking it. But if you’re not ready to follow their lead, thanks to FATCA and other intrusive laws, it’s become increasingly difficult to legally maintain financial privacy from the long, crooked fingers of Uncle Sam.

Reprinted with permission from Nestmann.com.

The post Uncle Sam (and the Taxman) appeared first on LewRockwell.

Leave a Reply