The Legacy of China’s One-Child Policy

“Both my husband and I were youths in Mao Zedong’s era,” says 63-year-old Wang Aiying. “We abided by the Party’s words, answered the Party’s call of duty and supported the Party’s policy.” Among other things, that meant adhering to the one-child ruling, an act of obedience that would, in 2015, leave Wang in deep despair. After her son died, she became a shidu fumu, one of a growing number of bereaved Chinese entering their twilight years without the emotional and financial support of a child.

Her son, Chang Jia, was nearly not born at all. In 1980, having been pregnant for just a few weeks, Wang, who had previously suffered a miscarriage and wasn’t taking any chances this time around, was in hospital when managers from her place of work came to visit. She had not been given approval by her employer, the Yu Opera House, in Handan, Hebei province, to have a child, they said. “They told me that it wasn’t my turn,” says Wang. “‘What?’ I said. ‘What do you think this is? That I can return the goods?’”

Wang, 26 at the time, successfully argued for the right to have her baby, but after the birth of her son, she was asked by her employer not to have a second child. She agreed and received a certificate for having just one child. “I felt honoured back then, because I listened to the words of the Party,” says Wang. Having five siblings herself, she accepted that the one-child policy was for the greater good and that young people should follow its guidelines.

Buy Silver at Discounted Prices

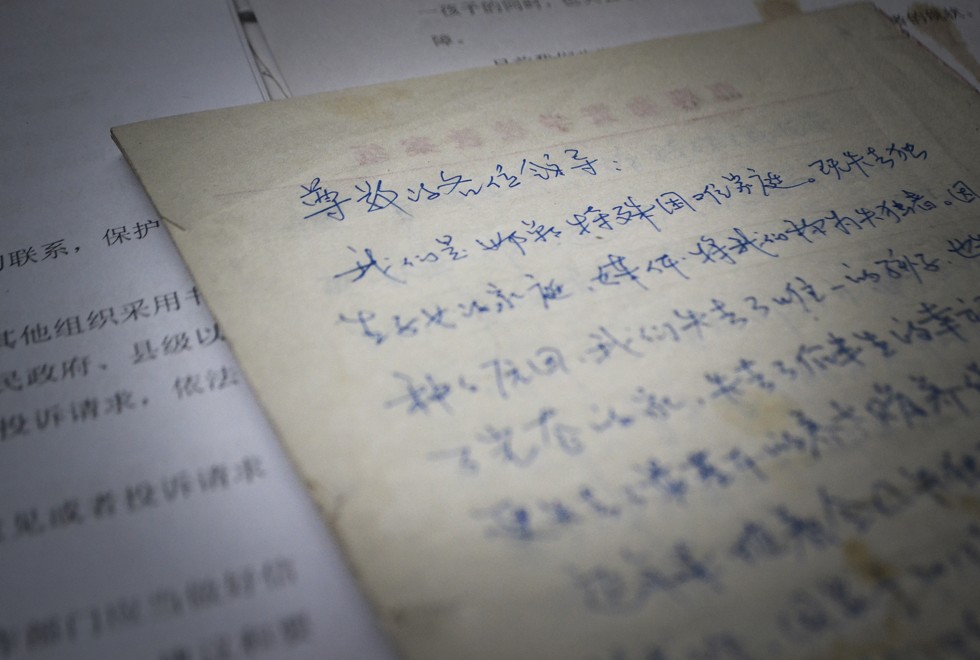

Zhao Bingyi’s petitions to government requesting more support for shidu parents. Picture: Fan Liya

In 2012, Chang was diagnosed with liver cancer. He did not respond to treatment and, two years ago, he died, at the age of 35. Wang was distraught and she is now childless. She and her husband, who were both laid off before retirement age, were suddenly facing old age without support from the next generation.

Shortly after her son died, Wang applied for the 3,000 yuan retirement subsidy available to one-child parents but she encountered many obstacles. Because she had been laid off, in 2003, she was told she was not qualified for the retirement subsidy. “I don’t have money, nor do I have my son,” says Wang, weeping. “Why did I need to go here and there for all kinds of approvals to get the subsidy?”

That was Wang’s first experience as a shidu parent. Meaning “lose only”, shidu is a term that has been used by the media since 2010 to refer to parents who have lost their only child and are no longer able to have another. According to a 2013 report by the China National Committee on Ageing, a government branch overseeing the country’s increasingly grey society, there are at least one million shidu parents in China, and the number is increasing by 76,000 a year.

.As shidu parents of the first generation of the one-child policy are now in their 50s and 60s, many are becoming increasingly concerned about old age without a child to rely on. And they often find themselves the object of scorn.

“People sometimes humiliate me because my son died,” says Wang. In early April, she says, her electric bicycle was stolen from the parking rack at the bottom of her apartment block. She accused the security guard of negligence, only to be cursed as being someone who will “die without any descendants”.

Wang’s husband, 67-year-old Chang Shunde, has barely recovered from a cerebral infarction he suffered in 2010. He walks unsteadily and cannot talk or hear clearly. While listening to his wife, he cries and tries hard to say something. It’s not clear what. “I feel especially sad when I need help in my daily life,” says Wang.

The post The Legacy of China’s One-Child Policy appeared first on LewRockwell.

Leave a Reply